ADENOMIOSIS: the Cinderella of gynaecological diseases

Reading Time: 6 minutesAt our clinic, we are highly specialised in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. This article focuses mainly on the diagnostic part, while the therapeutic aspect will be dealt with in a separate article.

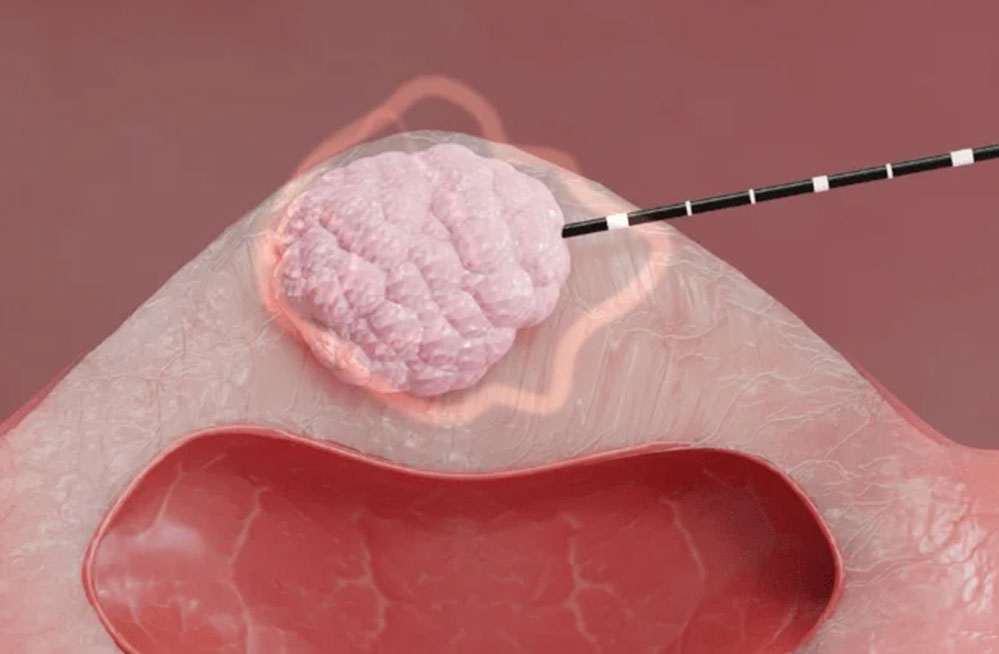

We can, however, anticipate that in our department we have introduced new minimally invasive surgical methods, such as radiofrequency or microwave thermo-ablation, which promises to be a new and revolutionary method for treating adenomyosis (you can find articles specifically dedicated to thermo-ablation in the blog).

Just as the introduction of drugs belonging to the category of oral GnRH antagonists will be an effective new therapeutic tool for this pathology of the uterus

From the Latin adeno, gland, -my, muscle and -osis, irregularity and disorder. Adenomyosis is a benign uterine disease characterised by the presence of heterotopic endometrial glands, stroma in the myometrium and reactive fibrosis of the surrounding smooth muscle cells. Over the past 80 years, numerous theories have described how adenomyosis develops. Currently, the most accepted hypothesis of pathogenesis is that adenomyosis originates from invagination of the base of the endometrium into the myometrium. This invasion of endometrial tissue into the myometrium results in a volumetric increase of the uterus and is associated with a number of symptoms such as abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhoea and sometimes dyspareunia. Another possible theory is that adenomyotic lesions are due to metaplasia of mullerian remnants or differentiation of adult stem cells. Both of these theories may explain how parity may be a risk factor for the development of adenomyosis. Pregnancy may facilitate the extension of the endometrial lining into the myometrium due to the invasive nature of the trophoblast. Pregnancy may also create a highly oestrogenic environment in which ectopic endometrial foci may develop.

Reports show that about 20% of adenomyosis cases involve women under 40 years of age and 80% between 40 and 50 years. Adenomyosis is completely asymptomatic in about one third of cases. The most frequent symptoms in the remaining two thirds are menorrhagia (50%), dysmenorrhoea (30%) and metrorrhagia (20%). Dyspareunia can also be a disorder. Diagnostic techniques have developed to become less invasive over the years. It has been reported that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a sensitivity ranging from 46% to 90% in detecting adenomyosis. On MRI, the most important finding in the diagnosis of adenomyosis is the thickness of the junctional zone greater than 12 mm. Its main limitation, however, is the absence of a definable junctional zone in approximately 20% of premenopausal women. Transvaginal ultrasound has a similar sensitivity (89%) to magnetic resonance imaging and allows for the detection of characteristic features of adenomyosis; therefore in clinically suspected cases of adenomyosis, transvaginal ultrasound should be considered the primary diagnostic tool. In fact, nowadays, transvaginal ultrasound is the first-line imaging method for diagnosing adenomyosis. It has been shown to be sufficiently accurate when using the histopathology of hysterectomy specimens as a reference standard. It has been reported that three-dimensional (3D) transvaginal ultrasound improves the diagnostic accuracy of adenomyosis, as it allows visualisation of changes in the junctional zone in greater detail than two-dimensional (2D) ultrasound. Until now, there is a lack of a uniformly accepted or validated system to diagnose or classify the severity of adenomyosis based on imaging findings. In 2015, the international Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group published a consensus on what terminology to use to describe ultrasound images of adenomyosis. In 2019, the MUSA group suggested a uniform classification and reporting system to be used to describe morphological changes in adenomyosis and its extent. The basic ultrasound signs for adenomyosis are divided into direct and indirect ultrasound signs. Direct features indicate the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium; indirect features are those secondary to the presence of endometrial tissue in the myometrium, such as muscular hypertrophy (globular uterus) or artefacts, e.g. shadows. The experts also agreed that the assessment of the junctional zone is useful in cases of uncertainty about the diagnosis. A regular and uninterrupted junctional zone indicates the absence of adenomyosis. The experts suggested assessing the regularity of the junctional zone in several planes using 3D ultrasound.

Regarding direct ultrasound signs:

Myometrial cysts, MUSA criteria define cysts as: 'rounded lesions within the myometrium'. The contents may be anechogenic, of low echogenicity, ground-glass appearance or mixed echogenicity. The cysts may be surrounded by a hyperechogenic rim. Any size of a myometrial cyst is relevant (no minimum or maximum size). The use of colour Doppler is recommended to distinguish blood vessels from myometrial cysts.

Hyperechogenic islands/areas, defined by the MUSA criteria as "hyperechogenic areas within the myometrium that may be regular, irregular or poorly defined". Hyperechogenic islands should have no connection to the endometrium. A minimum distance from the endometrium has not been defined as it would be arbitrary. The same applies to a minimum diameter or a certain number of hyperechogenic islands. They are a direct feature of adenomyosis, as they represent the ectopic endometrium within the myometrium.

Echogenic subendometrial lines and sketches, defined by the MUSA criteria "hyperechogenic subendometrial lines or sketches may be observed that interrupt the junctional zone. Hyperechogenic subendometrial lines are (almost) perpendicular to the endometrial cavity and are in continuum with the endometrium. Any form of invasion of endometrial tissue into the myometrium may be a sign of adenomyosis, even if it does not present the appearance of lines or sketches.

Indirect ultrasound signs, on the other hand, include the following findings:

Globular uterus, is present when the myometrial serosa diverges from the cervix in at least two directions (anterior/posterior/lateral), instead of following a trajectory parallel to the endometrium, the measured diameters (length/width/depth) of the uterine body are approximately equal. This results in the typical spherical shape of a globular uterus. There is consensus that this sign may be a false positive if a fibroid or intracavitary abnormality is present and that the globular shape describes the shape, not the size, of the uterus.

Asymmetrical myometrial thickening, the ratio of anterior to posterior wall thickness is calculated. A ratio of about 1 indicates that the myometrial walls are symmetrical while a ratio well above or well below 1 indicates asymmetry, although this can also be subjectively estimated. Potential diagnostic errors regarding the assessment of asymmetry are transient uterine contractions or the presence of uterine fibroids

Fan-shaped shadowing, defined by the MUSA criteria as "the presence of hypoechogenic linear stripes, sometimes alternating with hyperechogenic linear stripes". A shadow must be present behind the myometrial lesion, which is best assessed in greyscale mode. Diagnostic problems can be caused by other shadow-generating lesions, such as fibroids or fibrosis in a caesarean section scar

Intralesional vascularisation, which is characterised by the presence of blood vessels perpendicular to the uterine cavity that pass through the lesion. Translesional vascularisation appears to be present in diffuse adenomyosis, but that circumferential vascularisation, which is typically observed around fibroids, may also be present when an adenomyoma is present. Experts agreed that, although intralesional vessels may be present in fibroids, translesional vascularisation, i.e. the vessels passing through the lesion, is not visible in fibroids. For this reason, this characteristic is suitable for distinguishing adenomyosis from fibroids.

Irregularity of the junctional zone, the junctional zone may be irregular due to cystic areas, hyper-echogenic spots and hyper-echogenic sketches and lines. The extent of the irregularity of the junctional zone is expressed as the difference between the maximum and minimum thickness of the junctional zone. The extent of irregularity is reported as a subjective estimate of the percentage of the junctional zone that is irregular (< 50% or ≥ 50). The junctional zone should be assessed using 3D-TVS in the sagittal, transverse and coronal planes, but that there is no scientific evidence to recommend a cut-off for the thickness of the junctional zone to diagnose adenomyosis.

Interrupted junctional zone, the interruption of the junctional zone when part of the junctional zone cannot be visualised. An irregular, interrupted or non-visible junctional zone indicates that adenomyosis may be present (indirect feature) and should prompt the ultrasound examiner to examine the myometrium for direct features.

The invasion of endometrial tissue into the myometrium should be interpreted with caution in older and postmenopausal women as it may be a sign of malignancy and not adenomyosis (subendometrial sketches and lines).

Adenomyosis is often diagnosed in the presence of three or more ultrasound criteria. To date, transvaginal ultrasound remains the most widely used technique for even early diagnosis of adenomyosis.

At our clinic, we are highly specialised in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis.

At our department we have introduced new minimally invasive surgical methods, such as radiofrequency or microwave thermo-ablation, which is a new and revolutionary method for treating adenomyosis (you can find articles specifically dedicated to thermo-ablation in the blog).

Bibliography

Andrea Etrusco, et al. Current Medical Therapy for Adenomyosis: From Bench to Bedside. Drugs 2023 Nov;83(17):1595-1611. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01957-7. Epub 2023 Oct 14.

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9(9):CD000400.

Gaby Moawad, et al. Adenomyosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022 May;39(5):1027-1031. doi: 10.1007/s10815-022-02476-2. Epub 2022 Mar 28.

Harada T, et al. The Impact of Adenomyosis on Women's Fertility. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2016;71(9):557-568. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000346. (check it out)

Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7):CD001751

M J Harmsen, et al. Consensus on revised definitions of Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) features of adenomyosis: results of modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Jul;60(1):118-131. doi: 10.1002/uog.24786.

Paolo Vercellini, et al. Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility. Fertil Steril. 2023 May;119(5):727-740. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.03.018. Epub 2023 Mar 21.